A quick post to spread the word about my new favourite little bookshop in central Vietnam. Chili Books has been open now for about a year at 96 Trần Phú street in Da Nang.

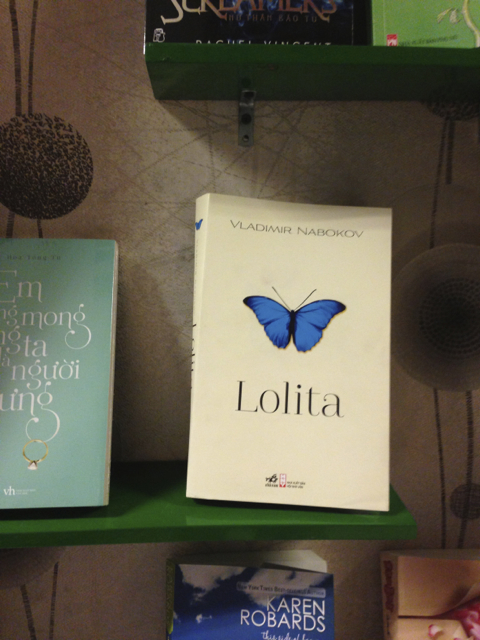

Pretty much one whole wall of the small shop is taken up with Vietnamese translations of international literature. It is an impressive selection for such a small shop, and one of the best showcases I’ve seen lately of the breadth and depth of international literature now available in Vietnamese. Kafka and Nabokov, Kiran Desai and Brett Easton Ellis, John Steinbeck and Herman Hesse, Patrick Süskind and a whole bunch of other more recent authors.

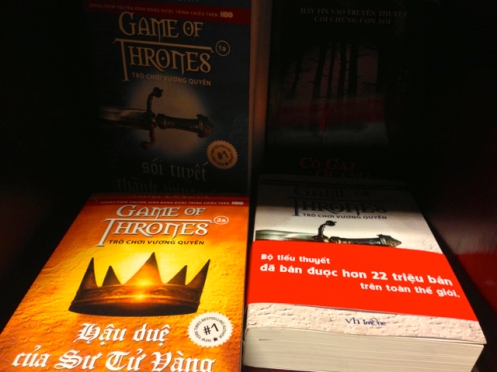

The Game of Thrones series is there, together with J.K. Rowling’s post-Potter book The Casual Vacancy, all in Vietnamese. It looks like the translation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, published in Viet Nam earlier this year, has already sold out.

There is a small selection of English-language books at the rear of the shop, heavily weighted towards Nobel Prize winners and similar authors. Novels I’ve read and others that I ought to have read. I’m impressed to find works by Doris Lessing and Jorge Luis Borges here.

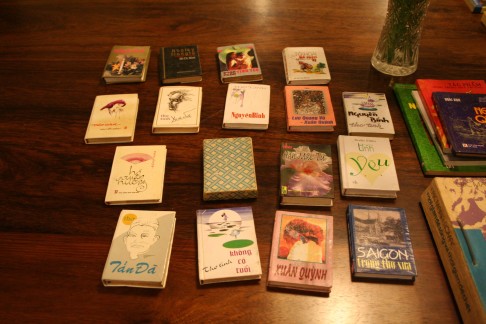

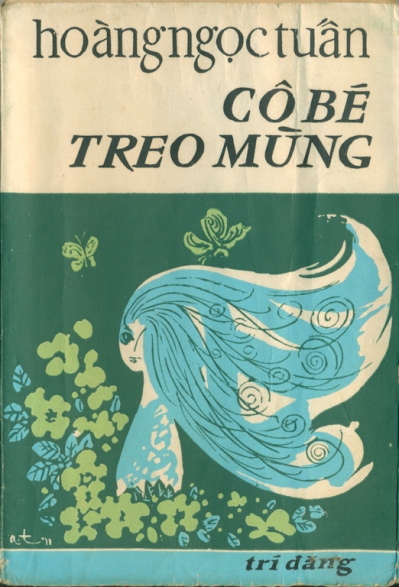

Just when I’m wondering if there are any works from Vietnamese authors, I hit the other long wall, which is dominated by a relatively small but very fresh and thoughtful selection of recent Vietnamese fiction, supplemented by a few poetry collections. There is also a book exchange for used books. Towards the rear on this side there is a decent selection of Vietnamese and translated non-fiction works, sitting alongside a bunch of children’s books in translation, including some of my childhood favourites by Astrid Lindgren, Roald Dahl, E. Nesbit and A.A. Milne.

I asked Linh, the owner, what inspired her to open Chili. She answered simply that she had studied literature and loves books. Which is pretty much the most obvious and best reason to open a bookshop, I guess. The slogan of the shop, displayed in English above the entrance and on their Facebook page [link], is “From book to soul”.

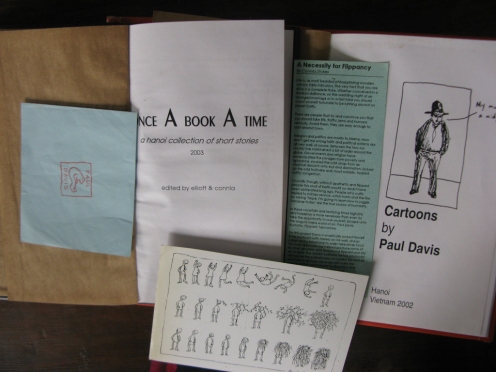

So what did I buy? Well, first of all a large volume of works by poet Nguyen Duy, taken from his various collections published from 1973 through 1997. And I couldn’t resist the Vietnamese translation of Vietnamese-Australian writer Nam Lê’s award winning 2008 collection The Boat (Du thuyền). I have the English original, but hadn’t realized it had been published in Vietnam in 2011.

I balanced this with the English translation of Nguyễn Ngọc Thuần’s 2002 children’s book Open the Window, Eyes Closed (Vừa nhắm mắt vừa mở cửa số). I’ve been on the lookout for this since seeing some excerpts published in an online newspaper.

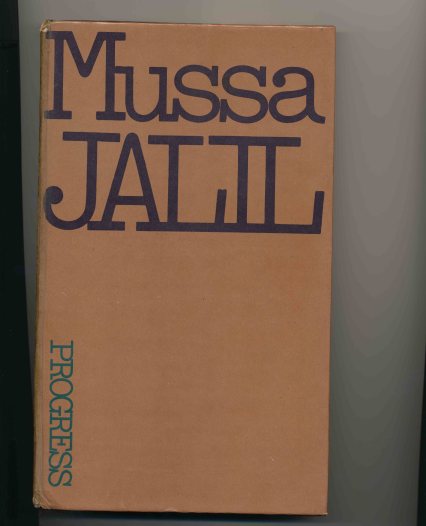

I also took with me what was probably the oldest book in the shop, a non-fiction work in English printed in 1979 by Progress Publishers, Moscow. As previous posts attest, I’m somewhat obsessed with their books. The Nearest neighbor is 170 km away, by Dutch author Dick Walda, is a sympathetic account of the USSR aimed at a Western European audience, based on the author’s repeated visits.

Skimming the book, it is interesting to see how Walda dealt with the rather thorny issue of State censorship in the USSR. He recounts a discussion with poet Bella Akhmadulina about a poem of hers that had recently been rejected by publishers for being too ‘decadent’. She questioned the decision, but argued for the vitality of poetry in the USSR at that time: “I am convinced that real talent will win through against the bureaucratic obstacles which are sometimes put up”. Walda follows this up with an account of another discussion, this time with poet and writer Bulat Okudzhava:

“Okudzhava was amused when I told him that in the Netherlands there is a committee to fight censorship which, among other things, seeks out books that have not been published in the USSR and publishes them in the West. Okudzhava told me about the contacts he had had with similar unsavoury champions of the freedom of the press. He said he suspected strongly that such people were motivated by the prospect of fat profits for which goal they are not above playing on the pride and ambition of some Soviet writers…”

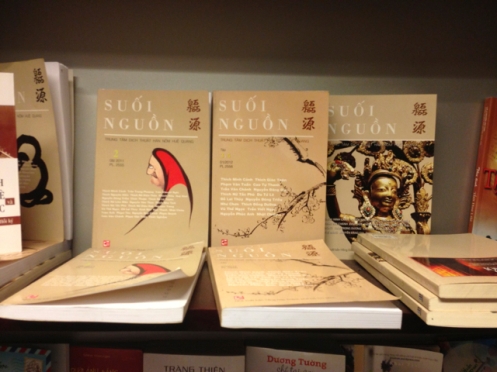

The final set of books I came away with was the first five volumes of the journal Suoi Nguon, published in 2011 and 2012 in Ho Chi Minh City. Suoi Nguon is produced by the Trung Tâm Dịch Thuật Hán Nôm Huệ Quang (Huệ Quang Centre for Hán Nôm translation). Hán Nôm is a script used in Viet Nam until the 1920s for writing literary works, using both standard classical Chinese characters as well as other characters to represent vernacular Vietnamese vocabulary. The Centre is based in Huệ Quang Pagoda in Tân Phú district of Ho Chi Minh City.

The scope of the journal seems to be much broader than the study of Hán Nôm, however:

“Suối Nguồn is an academic and ideological product based on the study of Hán Nôm and the fields of Literature, History, Philosophy and Religion, contributing to upholding Buddhist dharma, preserving the national literature and building the culture of the nation, adapted to the new conditions of the times and the specific historical circumstances of the current period of the country.” (From the Foreword, my translation).

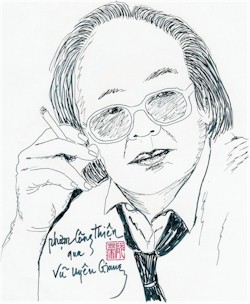

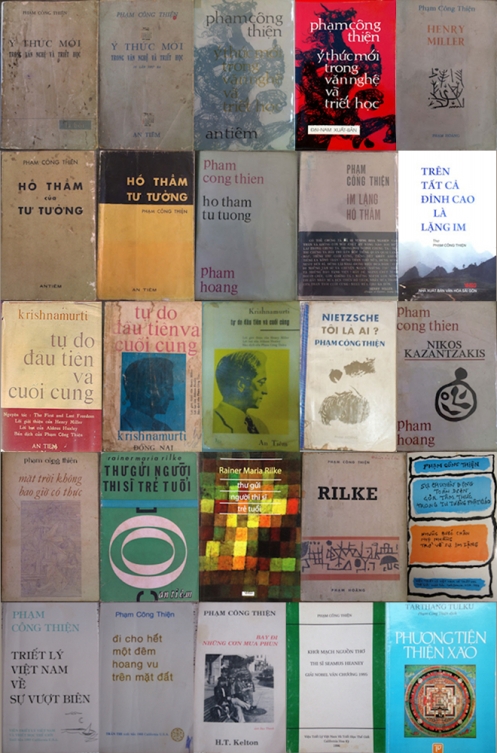

The journal very much reminds me of Buddhist publications from Sai Gon in the 1960s and associated with Vạn Hạnh University, where lecturers and writers like Thích Nhất Hạnh and Phạm Công Thiện sought to bridge Eastern and Western philosophy and to apply a kind of engaged Buddhism in the context of politics and violent conflict at that time.

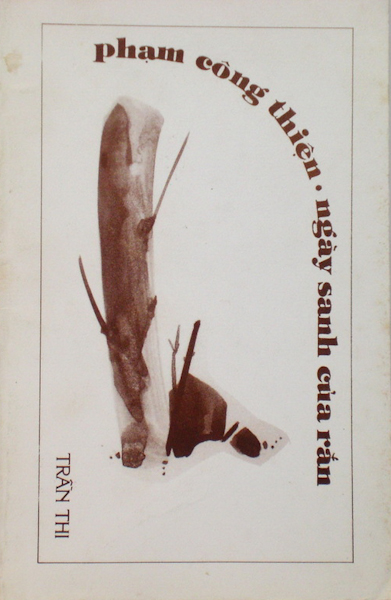

The connection seems to be more than just in the style: the Foreword of the first issue was written by Thích Nhất Hạnh himself, and includes an article on Phạm Công Thiện, exploring his poem Bất nhị and littered with references to some of Phạm Công Thiện’s prime literary interests, including Satre, Heidegger, Neitzche, Krishnamurti, Henry Miller, Nikos Kazantzakis and Phạm Công Thiện’s own contemporary Bùi Giáng.

So that was my visit to Chili Books, and a bit more besides. It reminded me of how much I love small bookshops, where you can least glance at just about every book in the place in a single visit. Chili has an international feel, with an up-to-date selection of translated titles and black-and-white pictures of famous foreign authors above the shelves. It forms its own small world in downtown Da Nang, its borders defined by the careful selection of the works on sale. If you are in the area, go and take a look.